I’ve always been drawn to stories that were a bit dark. In particular, dark tales with a sliver of light running through them or where moral qualities are sorely tested.

All of which suits crime novels, with odds stacked against the protagonists and pressures, external and internal, mounting up, all building up to a thrilling climax. Social issues and an atmospheric setting can frame, and give a wider meaning, to the story.

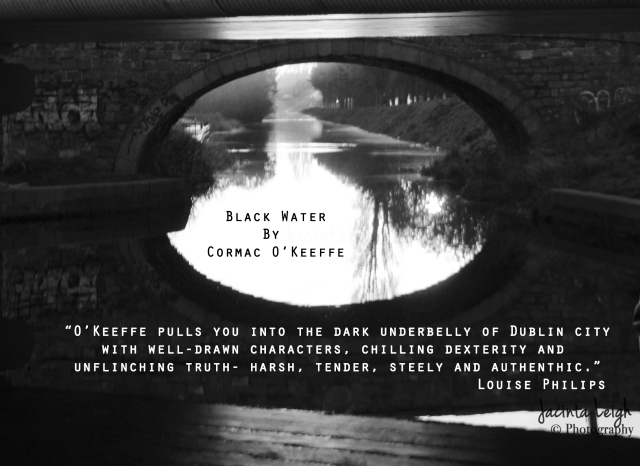

Well, that’s the ideal – and it was what I wanted to do with my debut novel Black Water. (Not that I had a specific plot initially to do that, only some characters and a setting, that being along a canal.) The story was dredged out of my soul and hauled onto the banks of the world.

It took eight long years of toil and effort, rejection and pain, but ultimately delight and the stuff of dreams.

Black Water was published in April 2018, thanks to Black and White, an independent publisher based in Edinburgh. They saw something in it and took a punt. Thanks to Ali, Campbell and editors Graham and, in particular, Emma. (Thanks to Tim Bingham for pics on the night of the launch.)

Me in a state of shock outside Dubray Book Shop on Dublin’s Grafton St the night of the launch. Pic: Tim Bingham

There are many people who got me to this place, including the writers at the Irish Crime Fiction Group (in particular, organisers Carolann Copland and Laurence O’Bryan), authors Andrea Carter, Ann O’Loughlin and Louise Philips. Hats off to ghost reader Dearbhail McDonald, friend and publicist Peter O’Connell and scout, event organiser, author and all-round good egg Vanessa O’Loughlin, and my agent, Ger Nichol. Also, cheers to Gill Hess for the PR and sales.

Crime Fiction Group gang: Jackie Walsh, Susan Condon and (famous author) Patricia Gibney at my launch

Special thanks to my wife, Jacinta, who helped, pushed and prodded – and had hugs on hand through the hard times.

I had no idea how the book would be received. To me it was a bit different; it didn’t really fit existing moulds. It was not a psychological thriller or a domestic noir, nor was it a classic police procedural. But it did combine elements of a thriller and a procedural.

Here’s what a couple of book bloggers thought…

“Black Water is an astonishing debut that literally took my breath away.” https://www.writing.ie/readers/black-water-by-cormac-o-keeffe/

“Black Water is a novel that opened my eyes and broke my heart.” https://stephsbookblog.com/2018/04/20/black-water-by-cormac-okeeffe-blog-tour-review/

“Even among the stellar crime fiction that’s been published recently, Black Water stands out.” http://www.theliteraryshed.co.uk/read/the-literary-lounge/black-water-an-entree-into-dublins-underworld

“An intensely addictive reading experience, one that will stay with you long after you turn that final page. Terrific stuff.” http://lizlovesbooks.com/lizlovesbooks/black-water-cormac-okeefe-blog-tour-review/

“A novel that stands out from the rest, with real depth and intensity, and a narrative heavy with brilliant imagery. It cleverly balances social comment with a deftly realised plot that is intense and fast paced.” https://mybookishblogspot.wordpress.com/2018/04/10/blogtour-black-water-by-cormac-okeeffe-cormacjokeeffe-bwpublishing-linalanglee/

And these were some of the reviews in the media..

Irish Times: “A compelling work of darkest noir” https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/the-best-new-crime-fiction-1.3459742

Irish Independent: “A searing debut thriller”

Irish Examiner: “Violent and gritty, this debut sings with authenticity. I couldn’t put it down.”

Books Ireland: “Generally, I find the grittier crime novels hard to stomach…but this debut blew me away.”

And here are a few other links to reviews

And here are a few other links to reviews

UK Crime Review: “Black Water moves at almost breakneck pace and is brilliantly plotted and totally compelling.” http://crimereview.co.uk/page.php/review/6361

The Student: “In the midst of the gritty events, there are beautiful descriptive passages and examples of humanity, tenderness and normality. This dynamic, the possibility of hope and improvement, is what draws the reader in and maintains their interest.” http://www.studentnewspaper.org/black-water/

But this one topped the year for me – getting into the Best Crime Fiction of 2018 in the Irish Times https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/the-best-crime-fiction-of-2018-1.3722683?mode=amp

2018 was a special year. A festive slice of darkest noir to you all and best of luck in 2019 to readers and writers alike.

![writers_block_400[1]](https://cormacokeeffecrime.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/writers_block_4001.gif?w=640)

![a24b2df4e3a5b37f0acdecc0a015116b[1]](https://cormacokeeffecrime.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/a24b2df4e3a5b37f0acdecc0a015116b1.jpg?w=640)